Healthy nutrition is a concept we are all familiar with. This generally means consuming ample amounts of the nutrients which are beneficial for health (fibre, protein, vitamins, minerals), whilst limiting nutrients which are not healthful (sodium, sugar, saturated fats). This also incorporates the concept of consuming the correct amount of energy. According to the WHO, there are currently 1 billion people across the world who have obesity, and the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) reports that the number of people affected by hunger in 2021 was 828 million. These two groups have vastly different needs, and what constitutes ‘healthy nutrition’ is equally disparate. Healthy nutrition messaging for individuals with overweight or obesity, and those who live in countries with high levels of overweight or obesity will, generally, predominantly focus reducing calorie intake, and campaigns and initiatives will revolve around limiting intake of fats, sodium, sugar, as well as cutting back fast-food or takeaway intake. Conversely, in typically less-developed countries, where undernourishment is a larger issue, programs aim to deliver calories, protein, vitamins, and minerals in a cost-effective way to prevent disease.

To witness this divergence in action, we need only look to national policies aiming to improve health:

The UK Government has introduced restrictions on food high in fat, sugar and salt (HFSS), which aims to reduce the amount that these are purchased, mainly by banning promotions on these items, and restrictions where these can be displayed.

Conversely, the World Food Programme recently, in March this year, signed a cooperation agreement with the Government of India in order to “build on India’s national priorities for food and nutrition security through strong cooperation with the government around capacity strengthening and technical support for national social protection programmes and government schemes.”

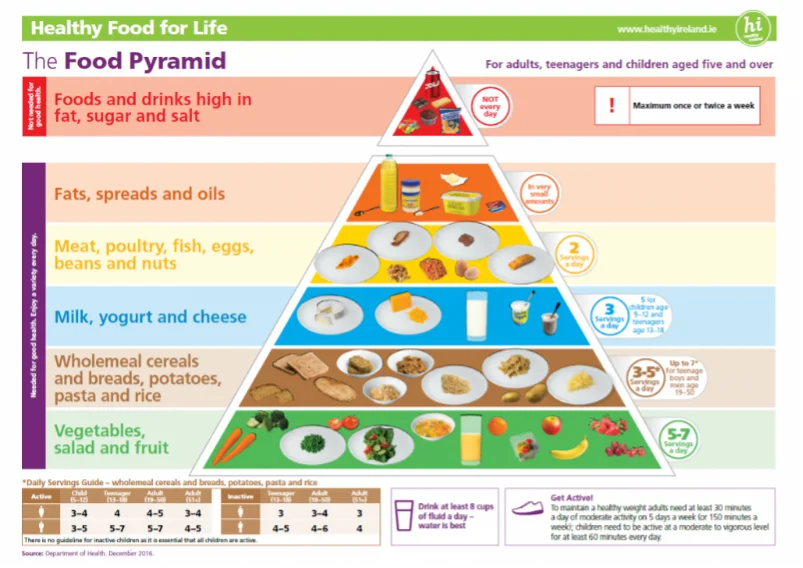

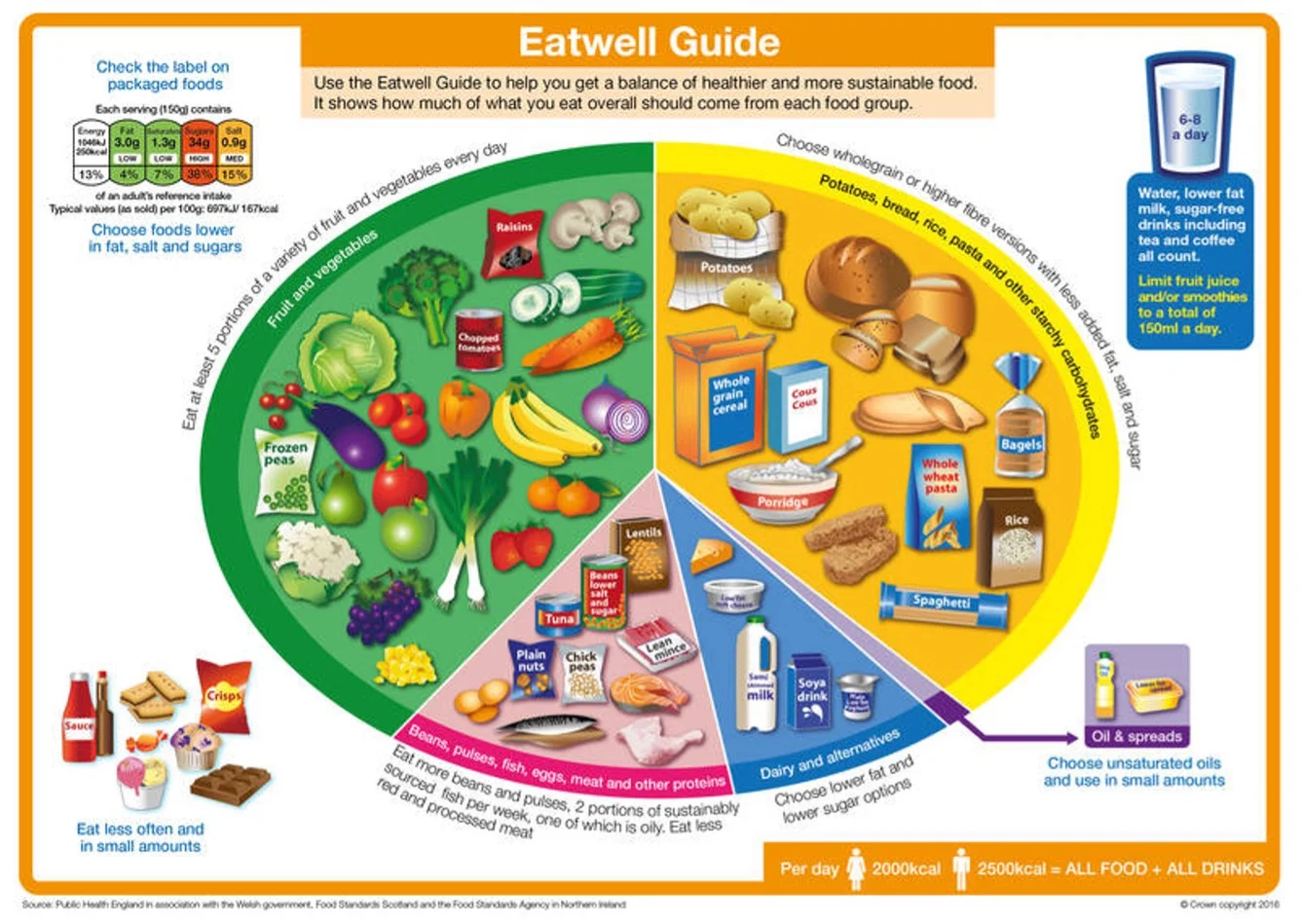

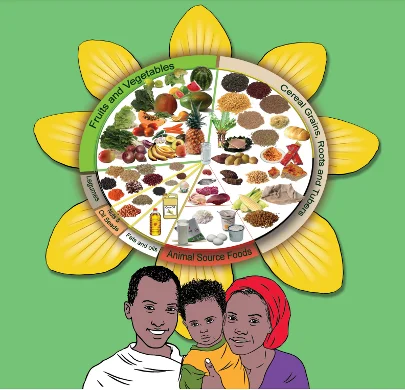

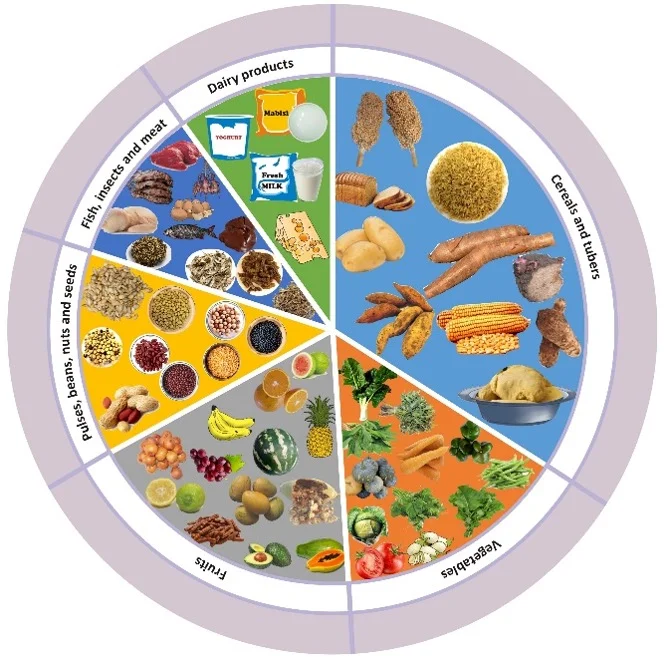

The inequalities in needs between nations is nothing new; dietary guidelines allude to the differing needs of different populations. As shown below, the food based dietary guidelines of various countries, such as food pyramids and ‘healthy eating plates’, encourage the consumption of cereals, fruits and vegetables, small amounts meat and fish, and limiting intakes of oil and sugary food sources. But if we take a closer look, we can see that the messages differ slightly; guidelines in European countries are formulated in the lens of the public health problems of non-communicable diseases, such as obesity, heart disease, and diabetes, whereas in other countries there is larger emphasis on regional variability, sustainability, and the sourcing of clean water, for example Ethiopia.

Albanian Food Pyramid

Irish Food Pyramid

Irish Food Pyramid

UK EatWell Guide

Zambian Food Guide

What do these guidelines have to do with sustainable nutrition?

As mentioned above, there is a disparity in needs between populations across the globe. An overwhelming number of individuals live with overweight and obesity, whereas on the other end of the spectrum, billions suffer from malnutrition. How to solve this disparity is an ongoing debate, with one school of thought advocating for the reduction or complete removal of meat products, which would help lower greenhouse gas emissions, and others arguing that whilst this may help achieve eco targets, this may not be optimal for human health.

As discussed recently in their Contribution of terrestrial animal source food to healthy diets for improved nutrition and health outcomes, the @FAO highlight how livestock play an important role in global nutrient intake and play an important role in agroecological transition, but this is based on the appropriate intake of these foods. Emerging evidence shows that greater species diversity in the diet is key to achieving both a nutrient dense and healthful diet as well as helping contribute to sustainability goals. We therefore must be mindful of our intake and incorporate a wide variety of foods from various sources, including plants, dairy and eggs, some meat, in a manner that is not wasteful. By following national guidelines, and adjusting for individual needs where appropriate, it is possible to consume in a way that is optimal for health yet helps prevent waste. This is just one small step in achieving sustainable nutrition. Whereas in certain parts of the world, intake is based on seasonality and local availability, in others, protein sources are far more limited, meaning mass production of those foods and little variation in intake. Incorporating seasonal appropriate intake of fruits, vegetables, and wider variety of protein intakes, we can work towards achieving sustainable nutrition targets.

Follow us and stay tuned for upcoming entries in our series on Sustainable Nutrition, where will we talk about the environment, Economic aspects of sustainable nutrition, and the importance of SocioCultural norms in addressing sustainability.