Hydration

Water is one of, if not the, most important nutrient we can consume.

Water is the largest constituent in the body and makes up the majority of our major organs; the brain is 75% water, kidneys around 81% and liver around 71%. The female body is approximately 50-55% water and the male body approximately 60%; we are more water than anything else!

Water is needed for health and proper physical function – it ensures the cells of the brain receive adequate oxygen, helps the digestion and absorption of nutrients from the digestive tract, and keeps our muscles and joints moving properly.

An average healthy person has enough stored energy in the form of muscle and fat to survive between 1-2 months without any food, but with no access to water, we could only survive around 3 days.

What is dehydration?

Dehydration (technically called ‘hypohydration’; dehydration is the process by which one becomes hypohydrated) is simply a lack of total body water, i.e., one has lost more fluid than they have ingested or replaced. Hydration levels are fluid – forgive the pun! – as fluid balance is under homeostatic control by physiological mechanisms that modify pathways to stimulate intake (for example thirst) and regulate excretion (for example sweating).

People can generally tolerate losses of up to 4% of total body water without severe symptoms beyond thirst, but between 5-8% can lead to dizziness, headaches, and fatigue, and up to and over 10% can lead to more physical and mental symptoms, such as fainting, confusion, and heart palpitations.

Further losses to the region of 15-25% are incredible risky, as this greatly increases the chances of fatality. Don’t worry though, it is difficult to become this dehydrated in normal conditions, only in extreme temperatures, usually combined with prolonged exercise (or outside work in these conditions), or during illness through high body temperatures, or loss of fluid through diarrhoea or vomiting. Regardless, be sure to be replenishing liquids throughout the day to avoid any negative consequences.

How do I know if I am dehydrated?

The early signs of dehydration are subtle, so it is important to be aware of them, especially if regularly consuming fluid is not a habit. We have highlighted the following symptoms which are suggestive of dehydration:

· Being thirsty or having a dry mouth

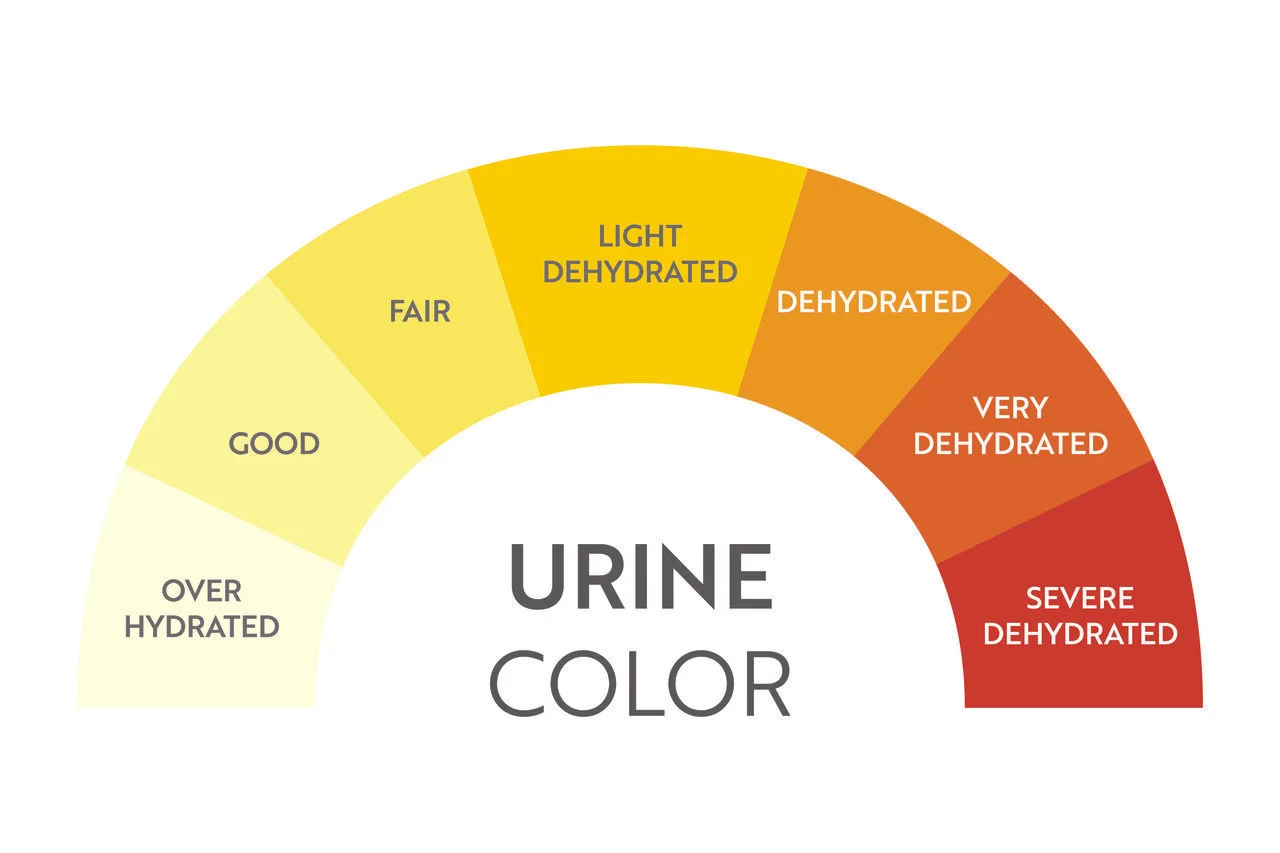

· Dark urine

· Headaches

· Fatigue and dizziness

· Dry eyes and/or skin

Please note, thirst is not a good indicator of hydration status, as thirst is usually delayed compared to one’s hydration status. Don’t wait to be thirsty to start drinking.

The urine chart below can help you assess your urine colour in order to see if you are dehydrated.

References

- Fleming, J., & James, L. J. (2014). Repeated familiarisation with hypohydration attenuates the performance decrement caused by hypohydration during treadmill running. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme, 39(2), 124–129.

- Healthdirect.com. Urine Colour Chart. Available from: https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/urine-colour-chart (accessed 21st July 2023).

- James, L. J., Stevenson, E. J., Rumbold, P. L. S., & Hulston, C. J. (2019). Cow’s milk as a post-exercise recovery drink: implications for performance and health. European journal of sport science, 19(1), 40–48.

- Latzka, W. A., & Montain, S. J. (1999). Water and electrolyte requirements for exercise. Clinics in sports medicine, 18(3), 513–524.

- Shirreffs, S. M., Taylor, A. J., Leiper, J. B., & Maughan, R. J. (1996). Post-exercise rehydration in man: effects of volume consumed and drink sodium content. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 28(10), 1260–1271.